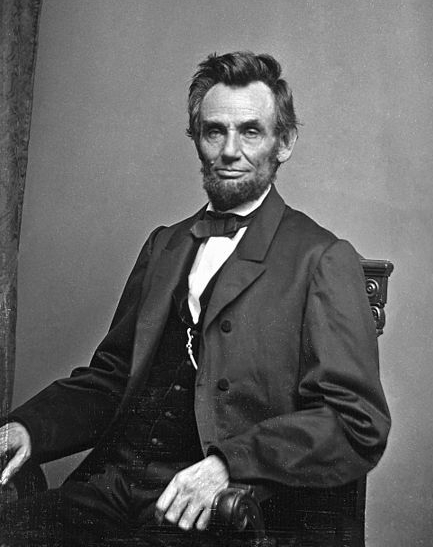

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, and the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, guaranteed citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws. The 14th Amendment declared that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

And yet these two amendments did not guarantee the right to vote to black citizens. And so in 1869 the 15th Amendment was proposed. It was hotly debated, supported by Republicans and opposed by Democrats. Several variations were proposed, and women’s suffrage groups were eager to include “sex” as one of the voting restrictions that would be banned. In the end, the women were disappointed. The amendment prohibited the federal government or any state from denying or abridging a citizen’s right to vote on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

This was the guarantee that black men were waiting for. The amendment was certified as duly ratified and part of the Constitution on March 30, 1870. It was widely celebrated, a story that I will come to later this year.

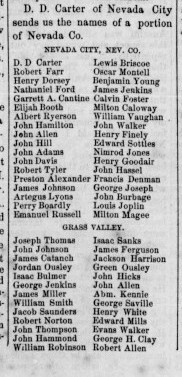

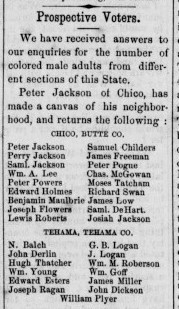

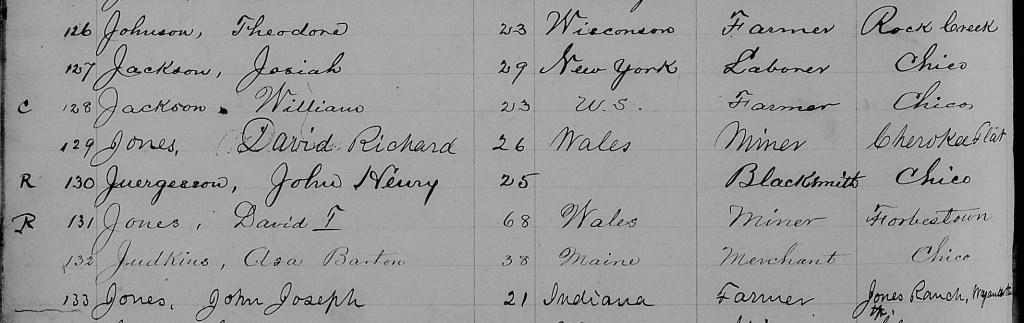

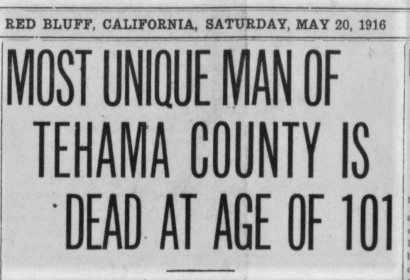

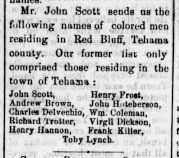

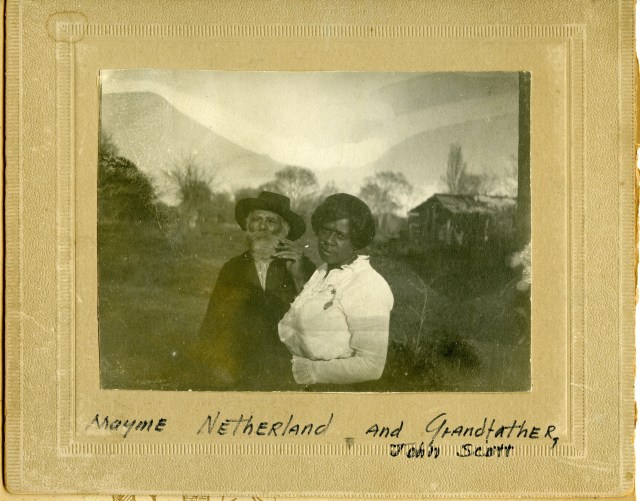

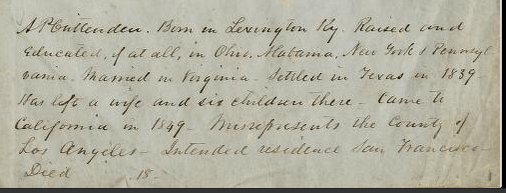

The Elevator newspaper sought out the names of prospective black voters in the lead up to the amendment in 1869. D.D. Carter, husband of journalist Jennie Carter, reported names from the sizable black community in Nevada County. John Scott, prominent black citizen of Tehama County, reported names from Red Bluff, as previously noted.

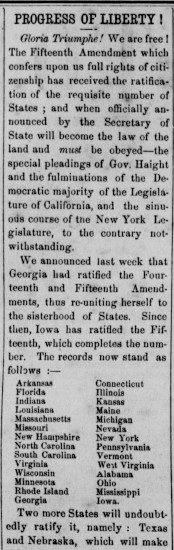

State by state, The Elevator kept track of the ratification process, the all-important “Progress of Liberty.” Look at the list of states below. Notice what is missing?

California did not ratify the 15th Amendment until 1962! finally catching up with the rest of the country. Of course, the refusal by the California legislature to ratify had no effect once the amendment took effect, and black Californians did obtain the right to vote. But at the time the Democratic governor and legislature, many of whose members came from the southern states, declined to ratify the amendment.

(It should be noted that the southern states that ratified the amendment, either did so because they were still controlled by Radical Reconstruction governments or were required to do so in order to regain representation in Congress. Most of them later enacted the Jim Crow laws that restricted black voting rights until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.)