Continuing my series on 19th century California politics–

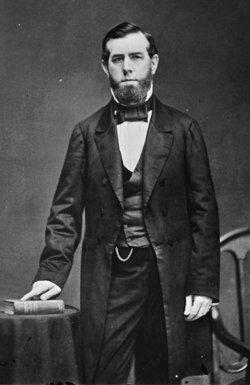

William M. Gwin was not the only man to come to California with political ambitions. David C. Broderick, another Democrat, came for the same reasons. But Broderick was was a Democrat of a different stripe.

Gwin aspired to be a Southern gentleman, but without a landed inheritance to sustain him. He got ahead by closely allying himself with Andrew Jackson and learning how to maneuver himself in the political world, acquiring land and slaves in the process.

David Broderick, the son of Irish immigrants, was raised in New York City. Like his father, he was a stonecutter, but he wanted to get ahead in the world. He read and studied ravenously and passed the bar. He joined the Democratic Party and became a protegee of the Tammany Hall gang, assiduously climbing the hierarchy of the party. He ran for Congress in 1846, but his brashness lost him the support of his party and he was beaten to the Whig candidate.

David Broderick, the son of Irish immigrants, was raised in New York City. Like his father, he was a stonecutter, but he wanted to get ahead in the world. He read and studied ravenously and passed the bar. He joined the Democratic Party and became a protegee of the Tammany Hall gang, assiduously climbing the hierarchy of the party. He ran for Congress in 1846, but his brashness lost him the support of his party and he was beaten to the Whig candidate.

Deciding he needed a fresh start, he joined the Gold Rush to California and arrived about the same time as his rival, Gwin. He wasn’t interested in mining, either. He could see that San Francisco was ripe with political opportunity.

He made the acquaintance of Colonel Jonathan Drake Stevenson, another New Yorker, who hired him to help run a private mint. San Francisco was in dire need of coinage (imagine how troublesome it was to pay for everything with pinched of gold dust), and there was no law against a private concern issuing money.

It turned out to be a gold mine, literally, for Broderick, because every five dollar gold piece had only four dollars worth of gold in it, and every ten dollar coin had only eight. What a way to make a fortune! Soon Broderick was buying land and getting into politics. At the same time he organized a volunteer fire company, gathering about him other Irishmen and New Yorkers. He was clever, quick, and fearless, and a natural-born leader. In a few months he rose to such prominence that in January 1850 he was elected to the state senate to fill a vacancy left by the resignation of another senator.

He was elected president of the Senate in April 1851, and then became lieutenant governor when Governor Peter Burnett resigned and John McDougal moved up to become governor. He was staunchly opposed to slavery and those, like Gwin, who supported it. His roots were in the working class and everything he did was to defend the rights of the working man.